An online laboratory for historians of SM&T

Saturday, December 1, 2012

HSS 2012

Monday, October 15, 2012

HSS Climate Survey

|

| www.toothpastefordinner.com |

I strongly support this action and I hope you'll take the time to complete the survey. I found the process of responding to be a really enlightening process. I found myself thinking in a broader way about the challenges that face our field and about the cultures of annual professional meetings. Although I enjoy and have found HSS meetings very productive, I definitely think there is room for improvement. Although the history of science supports diverse viewpoints, it is no secret that in other areas, particularly racial diversity, our homogeneity is plain to see. The Graduate Student and Early Career Caucus has done a great job improving the experience for more junior members of our society, but more efforts in this direction are also needed and, I think, would complement efforts toward increasing diversity. I was impressed by the degree to which the survey solicited written responses for clarifications and further thoughts, and I know those involved in putting it together would appreciate as full a response as possible.

Many thanks to Georgina Montgomery and our own alumna Erika Milam for spearheading this effort as the co-chairs of the Women's Caucus, and to Lynn Nyhart and the Executive Committee for their sponsorship. Many thanks as well to the graduate students who helped to organize and provide feedback early on, including our own Meridith Beck Sayre and Scott Prinster.

If you are a new student and have not yet joined HSS, there's no time like the present!

Sunday, October 14, 2012

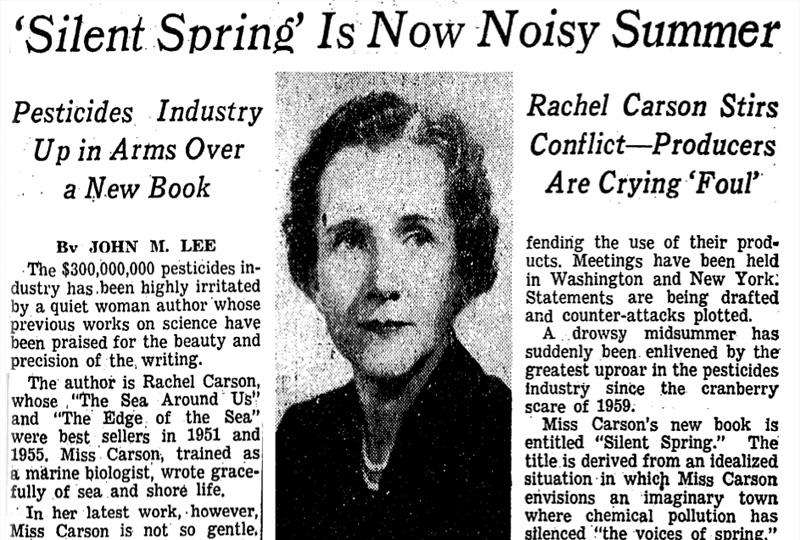

Kepler in Space

Friday, October 5, 2012

Sneaky CAPTCHA images contribute to the digitization effort

Recognize this image? Of course you do.

These goofy CAPTCHA images serve as the gatekeeper on many websites such as Facebook, Amazon, and Ticketmaster. Part of their function is to prove that the user is a human rather than a spamming computer, but thanks to the work of Luis von Ahm, a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon, the CAPTCHA is also contributing to the digitization of books and periodicals. Somehow I hadn't heard about this additional function, although I've filled out perhaps hundreds of these little boxes in the past several years... I blame my dissertator tunnel vision for this.

Despite advances in Optical Character Recognition (OCR), computers are not yet able to match the human mind's amazing ability to recognize symbols such as text, even when they are inconsistent, distorted, or poorly reproduced. Von Ahm has developed a version of the CAPTCHA program, called reCAPTCHA, in which the user is asked to type in two words instead of one. One of these words serves to confirm that the user is human, but the other is an image from a book or periodical, and our response helps to translate the image into text. Several users are given the same image, and if they consistently interpret the image as the same word, it is considered successfully converted to text.

Here's an article from the NPR website with more information about this program: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93605988

and also an article in <i>Science</i>:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/321/5895/1465.full?sid=e16c1bda-edda-462d-9198-baa2096672f9

Friday, August 31, 2012

Oh, Henrietta, we can live on forever...

Monday, July 9, 2012

The Higgs Boson walks into a church...

All three gentlemen should probably now dispense the standard church pun-ishment upon me. (I personally grew up atheist, so I have no idea what kind of trouble I'm in for.)

Congratulations, also, to all the hardworking physicists and engineers (you're welcome, Peter Galison) on the discovery of the particle-that-is-statistically-consistent-with-the-Higgs boson! We celebrate your great accomplishment by rejoicing in your use of Comic Sans in science.

(Image credit: it's floating around on facebook, but I can't find the original attribution. I'm not sure memes can have original attribution these days, but that's a whole other blog post...)

Saturday, June 9, 2012

History of Science films of note: Isaac Newton, Zombie Hunter

I guess historians of science like doing historical reenactments, like Captain Cook's 1768 expedition to observe the transit of Venus — but it's important to remember that we don't have a monopoly on doing history! According to The Hollywood Reporter, Rob Cohen, director of first Fast and the Furious and The Mummy 3: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor, will soon be teaming up with Rocky producer Gene Kirkwood to write and film a new movie based on Isaac Newton. Via The AV Club:

I'm sure that after writing the Principia, Newton needed something better to do, but I kinda doubt that hanging out with a pain in the rear like John Locke was one of them. On the other hand, if this upcoming movie is anything like Troy, we might want to make this required viewing for undergrad SciRev classes — with a shot whenever Newton's heterodox religion gets cut out of the script, or at least whenever we get to see Brad Pitt's pecs.“Cohen's story will focus on Newton's later years as the head of the Royal Mint, with his film casting Newton as a ‘detective’—perhaps one aided by Newton's older partner John Locke, as sort of an Enlightenment-age Lethal Weapon—with Newton devoting himself primarily to hunting down counterfeiters (and, should Cohen show any interest in actual history, slowly falling apart thanks to a system ravaged by alchemy-provoked mercury poisoning). ”

sources: THR, The AV Club, Lists of Note

image credit: National Geographic, The Michael Bayifier

Thursday, June 7, 2012

Transit of Venus

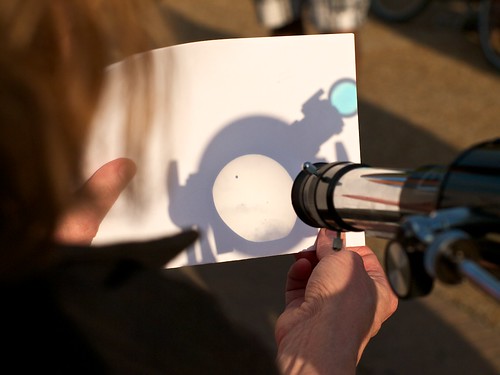

Aside from being a rare astronomical phenomenon, the Transit of Venus is significant for historical reasons. By combining precise observations of the Transit from multiple sites around the Earth, astronomers in the 17th and 18th centuries hoped to use the principle of parallax to calculate the distance between Venus and the Earth. If this distance could be determined, then the distances of all the planets from the Sun could be calculated using Kepler's law relating the period of a planet's orbit to its distance from the sun [video]. That is to say, scientists would finally know the absolute size of the solar system.

Scientists and explorers from Europe and America mounted expeditions to the far corners of the world to observe the transits of 1761 and 1769. This included the famous first voyage of James Cook, who set out from England to sail around South America at Cape Horn before heading on to the island of Tahiti in the South Pacific. After 8 months at sea, Cook and the scientific observers reached Tahiti and established a small observation post. After successfully recording their data, Cook and his crew continued on to explore the coasts of New Zealand and Australia before gradually making their way through the Indies and around the Cape of Good Hope on their way back to England.

Here in Madison, Mike, Florence, and Robin set up two telescopes at the Memorial Union Terrace. However the weather was mostly cloudy as the transit began. A dinner of beer, bratwurst, and sauerkraut helped our intrepid scholars ward off scurvy while waiting for the clouds to part.

Finally, about an hour into the transit, we began to see gaps in the clouds and sunlight breaking through in the west. As the sun came into view Mike and Florence quickly re-calibrated the telescopes.

One telescope had a solar filter that allowed viewers to look directly at the Sun and Venus, while the second telescope projected the image of the transit onto a sheet of paper.

As the clouds came and went, we attracted crowds of interested passers-by. People were grateful to have a chance to view the transit, and we all had a blast!

Click here for a full slideshow of the event.

Friday, June 1, 2012

A Thin Sheet of Reality: The Holographic Principle at the World Science Festival 2011

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

Other Blogs for Historians of Science, #12: "Science Minus Details"

*: Except those unreconstructed social-constructionist historians and sociologists of science.

Fortunately, there are other experts on science too, many of whom are more than happy to help us out in a bind. Many of these experts in science are called "scientists," or, as my friend, UW chemistry grad student, and science blogger Lee Bishop calls himself, a "professional science enthusiast." Lee's blog is helpfully called, Science Minus Details, and it offers exactly what it promises — unlike the titles of far too many historical monographs. Here is a taste, from "Dr. Licorice Explains Why Bisphenol-A is Scary".

"I recently made a chemical that smelled extremely familiar, but after numerous wafts, I couldn't quite tell what it reminded me of.

Me wafting the chemical I made. The chemical is the tiny bit of brown oil in that small clear jar in my left hand.

This puzzle went unsolved for days until my labmate Michelle used some of the chemical and was like, "Lee, have you noticed how that chemical you made smells just like licorice?"

I was like, "OMG, you solved it!!!!"

Victory Licorice!!!

Go have a look! While you're at it, Lee also helps run Madison's own Nerd Nite, a monthly-ish gathering of...well, if you're even thinking of going, you probably have an idea of what it is already.

Friday, May 18, 2012

Environment & Society Portal

|

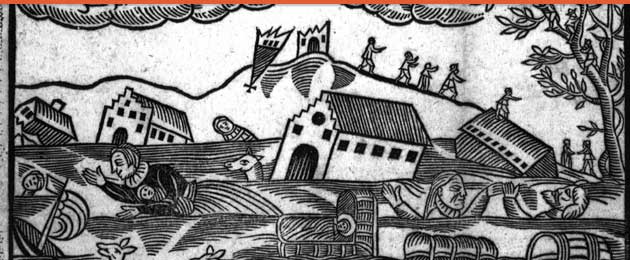

| Woodcut from broadsheet: "The Great and Terrible Flood," January 1651, from the Portal's Multimedia Library for environmental humanities |

|

| The Keyword Explorer links to articles and multimedia throughout the Portal |

Friday, May 11, 2012

From Jungle to Rainforest

This is just a quick post to share my review of Kelly Enright's The Maximum of Wilderness: The Jungle in the American Imagination, which was just posted on H-Environment, H-Net Reviews.

This is just a quick post to share my review of Kelly Enright's The Maximum of Wilderness: The Jungle in the American Imagination, which was just posted on H-Environment, H-Net Reviews.Becoming an H-Net reviewer is easy, and I highly recommend it. (Academic journals have a variety of book review policies. It's best to check a journal's website and contact the book review editor if you have questions.) It took several months before I was contacted to write a review, so don't delay contacting the appropriate H-Net editor if you are interested.

Writing a book review can be a rewarding experience. It allows you to take part in current scholarly discussions more rapidly than through articles or books, yet more formally than through a blog like this one. In particular, because H-Net publishes online, there is a very quick turnaround time. I also find that reviewing a book is helpful for clarifying my own ideas about the field. Because you have a responsibility to give the book a very close reading and produce a fair account, the process helps you achieve a better sense of your own interests and approaches, in addition to a deep understanding of the work you review. Of course, you also get a free* book!

*Not counting the time you spend writing!

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

This Fine Place So Far From Home

I was struck by how many people at AAR identified as coming from the working class -- it was significantly more than I've ever noticed in a group of historians. All of us who identified ourselves seemed to be wrestling with the same issues of isolation and feeling out of place, which I had assumed I was feeling mostly because of being a gay man in the academy. Many of the issues of feeling at home in academia are in fact similar for working class and LGBTQ scholars.

Perhaps the most prominent issue the book addresses is the sense of being pulled between two worlds. For many of us from the working class, getting an advanced degree is a source of pride for our family, but also a source of estrangement, as we are pulled increasingly away from our origins. Also, it's not easy to explain the value of spending several years pursuing a doctorate, which is a puzzling and extravagant use of time to my family. My experience is that my two (or three) worlds hardly intersect at all, and so it takes a lot of energy to keep investing in such divergent relationships. I've heard bilingual friends speak about their experiences in this way, too.

Also addressed are the issues that probably most grad students wrestle with, of feeling an impostor in the world of the intellect. I notice how some grad students who grew up in academic families seem to move through the program with such familiarity -- not that it's easier for them intellectually or emotionally, but that they don't immediately assume that it's because they don't belong there. I think that the level of self-doubt has a different meaning for people who come from outside this sphere.

And one struggle that I know I've not hidden well is how awkwardly working-class behaviors and values fit into the academy. Not simply speaking plainly, but being blunter, even belligerent, using more profanity, and "playing the game" with less grace -- all contribute to the experience of being out of place.

I think that having a working-class background has motivated me to look at my research differently, and approach my teaching differently, but I'm looking forward to reading this book and being reminded that, despite our feelings of invisibility, that quite a few people who have to navigate that experience of being an outsider. I also look forward to talking more with all of you about these dynamics.

Monday, April 16, 2012

Job Market Discussion

The History of Science brown bag for April 13th was an informal discussion on the job market, led by Alex Rudnick and Vicki Fama. We covered a lot of ground, but conversation focused primarily on the cover letter, teaching philosophy, the on-campus interview, and the value of post-docs. We mainly discussed issues that are pressing for students on or about to go on the market, but we hope to have future conversations about what one can do as a “younger” graduate student to prepare for the job search (Begin by reading this "The Professor Is In" post on the subject). Below is Meridith and Anna's summary of the sound advice doled out by our faculty:

Vicki started by noting that there is a lot of cynicism in the online dialogue about the job market. Certainly it's a tough market, but Mike Shank reminded us that it's been tight for historians of science for the last thirty years. So, what makes a strong application package? Mike was adamant (and other professors seemed to agree) that the cover letter is not only the first part of the application read, but can be a key means of weeding candidates out. It needs to be concise (no more than 2 pages), it should be addressed to the chair of the search committee, and it needs to be specific to the position that you're applying for. Tom Broman stressed the importance of being able to succinctly convey what your dissertation is about and show how your project can translate into future teaching and research. Judy Houck clarified that it's OK to have templates for cover letters; in fact, if you're applying to dozens of jobs (she applied to 100/year), you need to do this. For example, she created templates for positions in history of medicine, cultural history, and gender and women's studies. However, each letter should be tailored to the department in question, and should indicate how you fit the specific job, without being too defensive.

Anna Zeide asked about the types of positions one should apply to: is it wise to focus mainly on tenure-track (TT) jobs? Or is seeking transitional positions, like post-docs, a good strategy in some cases? Judy Houck said that it's typical for graduate students in the history of science and medicine to get post-docs before starting the TT search. She also pointed out that many of the alumni from our department who secured TT jobs right out of the program completed dissertations that were strongly relevant to fields beyond the history of science. One trend is that those who have done non-U.S. history have been more successful because of the far smaller pool of applicants. Mike Shank and Dayle DeLancey both felt post-docs are invaluable and are often the best strategy for everyone. Of course, there are different kinds of post-docs, but in general they can provide the opportunity for you to cut your teeth on teaching and work on publications. From the perspective of hiring committees, candidates with post-docs have been vetted by two institutions.

There seemed to be a fair amount of consensus that teaching philosophies are a fairly generic aspect of the package. They are normally not as tailored to a specific job as the cover letter, but it's good to mention courses offered in the department that you're prepared to teach. Judy Houck mentioned that when you're asked “How would you teach X,” people are often wondering what major works you would use in the class room, as opposed to your overall teaching style. The document itself should be broadly construed enough to demonstrate that you're flexible in your approach to teaching. Sue Lederer cautioned that one should not come off as someone who is SO committed to a certain kind of teaching philosophy that you appear unwilling to learn from future experience. She also said not to send the teaching philosophy unless an application explicitly asks for it. Andrew Stuhl pointed out that he aims to be a teacher first and foremost, so the teaching philosophy takes on greater importance as an element of the application package for students like him. He recommended the campus Writing Center's workshops on the teaching philosophy, and other elements of the application. As Anna Zeide nicely put it, it's an opportunity to express your voice and can be a “window into you.”

Finally, we discussed the on-campus interview. It's important to remember that the entire campus visit is an interview; dinners and causal conversations are just as crucial as talks or formal meetings. After all, the faculty is trying to decide whether or not you're someone that would make a good lifelong colleague. Generally one can expect to give a sample talk to the search committee and/or guest lecture an undergraduate course. You should treat these as chances to demonstrate your teaching abilities, not just discuss your research. Mike stressed that these are proxies for showing what kind of teacher you are: can you effectively teach the committee what your dissertation was about? Can you engage an audience? Judy noted that the interview process can be fun, as the focus is on you and your work, and that you're building connections with future colleagues, whether you end up in the position or not. However, you should also be prepared to ask questions of the faculty and make sure that you also show a sincere interest in your potential future work environment. Don't be too self-centered.

Micaela Sullivan-Fowler provided a piece of advice on the overall package: presentation matters. One should be make the effort to use high-quality paper, professional font, and pay attention to every detail.

- What to do now:

- Read widely about the state of our profession: The Chronicle of Higher Education (available in the library or in the Medical History department, The Professor Is In, and other blogs.

- Do your best to make wide connections, even outside your university, but make sure any reference letters you have are written by people who really know your work, and can offer specifics.

- Teaching classes can help your research. It gives you a sense of where your work fits into a larger picture, and helps you transition your dissertation into a book.

- Have a website. Update it!

- Cover Letter:

- Search committees are looking at large stacks of applications, and are hoping to weed some out. You have to make the initial cut, so make your cover letter opening as strong as possible. Avoid vagueness.

- In your cover letter, describe how you will complement the current department, with specific reference to faculty.

- Send your cover letter draft around to faculty and colleagues for proofreading/editing before sending out the official version. Mike Shank says he's happy to read!

- Job Interviews

- Job interviews aren't all intellectual; the committee also wants to get to know you and to see whether they want to have you as a colleague for the foreseeable future.

- At a campus visit, be able to answer questions like, "What do you like to do in your spare time?" Your answer to this indicates whether your lifestyle would be a good fit for the city/town in which the university is located.

- Search committee doesn't typically offer feedback; as it isn't politic to do so.

- Fundamentally, the most important part of getting a job is what kind of scholar you are and how you package that. It's about the work (and some luck. and time.)

Friday, April 13, 2012

Getting the Most Out of Regional Conferences

ThismorningI’mexaminingtheprovocationofarangeofAmericanresponsestothe1829textbookIntroductiontoGeologybyBenjaminSillimanSr.

This morning I’m examining (tiny pause) the provocation of a range of American responses (tiny pause) to the 1829 textbook (tiny pause) Introduction to Geology (tiny pause) by Benjamin Silliman Sr. (bigger pause)

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Teaching and the Job Market

We mainly discussed grading and leading sections; in fact, we didn't even make make it half way through the list of topics generated at the start. I mentioned a blog that some of us frequent, The Professor is In, which provides external advising to graduate students on or about to hit the job market. I also referenced this Chronicle article, which I promised to post. Dr. Karen Kelsky has some good, if tough, advice when it comes to teaching: 1) Be the sole instructor of at least one course by the time you graduate, b) minimize TA work, c) TAing is not a substitute for teaching your own course. This advice seems sound to me, but can be almost impossible to follow. The amount one TAs is often not a choice. Most grad students have to TA for at least a few semester during the course of their program as a means to earn tuition remission and support themselves, so the real question is how to manage time effectively while being the best teacher you can be?

Our conversation last week only scrapped the surface of this problem. People mentioned some techniques for reading/grading papers, and methods of involving students more fully in discussion, so that the burden of carrying a section does not fall solely on the TA's shoulders. I hope people will post some of their suggestions in the comments here!

Obviously, time management and balance is a perennial problem in academia that goes beyond TAing and teaching. The opportunity to talk openly and inclusively about these kinds of issues--with everyone from first year grad students to emeritus professors--is not only helpful, but special (for lack of a better word). Collegiality is one of the ways our department distinguishes itself and something I've come to deeply appreciate.

Both of the links I've shared here are also relevant to our April 13th brownbag on the job market: stay tuned...

Saturday, March 3, 2012

Just your browsing pleasure

Friday, January 20, 2012

A History of Science postcard form Berlin.

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Hazards of the Job, #1094A

R.F. Legget and T.D. Northwood of the National Research Council of Canada report that attending conferences is "one of the occupational hazards of scientific and engineering work in North America." Meetings like these tend to be very loud, presenting serious dangers to ears. Often, discussions cannot be fitted into business sessions, which forces delegates to "attend social functions where, in principle at least, more extensive discussions can take place." More chatter, more hurty ears.

Concerned about the volume of these conferences and associated sessions, Legget and Northwood sought to "determine whether the noise might constitute a health hazard for diplomats, bartenders, and other habitual party-goers."

In order to get an accurate measurements of the peak noise levels, the researchers are proposing to hold "a series of carefully planned experimental parties."

Yup.

Wednesday, January 18, 2012

Writing Groups

|

| Image credit: AAAS |

While the humor of the cartoon on the left is admittedly dark, I think it is so popular among dissertators in part because it actually offers an image of hope. We all fall off the proverbial writing wagon periodically. But have faith! The panic and despair of steps 3 & 4 do eventually give way to productivity.

Still, this image is misleading in one major way. The figure is alone. In my experience, the key factor in moving as quickly as possible through the inevitable steps 2-4 has been being part of a dissertator group.

Writing groups aren't just for the dissertation, of course. Back at Montana State, doing my MA, I was lucky to be part of a small, closeknit cohort. While we didn't meet formally as a writing group, we shared many, many drafts (and draughts--talking shop over beers was critical to honing my major arguments). That group kept me challenged and motivated through the entire MA process. Since beginning my PhD, I haven't had the same constancy––I've been part of several very different kinds of dissertator groups, and have gone through periods being without one. But hopefully telling you about my experience will motivate you to get a group if you don't already have one.

Dissertator groups come in different flavors. Each has benefits and drawbacks. Some involve members from all stages of the writing process. Others include people who are all at about the same point along the way. When I began to write my proposal, I joined a group in our department. For me, the most helpful part of that group was the fact that we were all at different stages. I got to hear what lay down the road for me and learn from more advanced grad students' experiences. Plus, the existence of people who were almost finished (!) proved that it really could be done: dissertations do get written! The downside there, though, was that successful, finished dissertators stop being dissertators––that can make it hard to sustain a group! So, "that" departmental dissertator group was really multiple groups, changing in membership and blinking in and out of existence. The groups I'm in now involve grad students at about the same stage and have been much more consistent in membership and stable over time. Of course, there is a chance that this sort of group can feel like a case of the blind leading the blind. But at their best, they provide a sense of solidarity that is immensely valuable. You are in it together. Others are facing the same questions and challenges that you are.

Some writing groups have members that share particular research interests, while others are more diverse. Right now I am a member of two different groups, one with a couple of history of science/environmental history folks, one with several "regular ol'" historians. (I don't necessarily recommend overbooking yourself like this, though I love both groups!) Although the range of individual topics is quite wide in both groups, it has been an enlightening exercise to pitch my work to such different audiences. In general, with a narrower group, you get somewhat more specific, on-target feedback about the content of your work. In a broader group, you will be constantly forced to answer that "so what" question.

Whatever the makeup of the group, it should probably include 3-5 dedicated people. With too many members, there's a risk that some will feel less committed and attendance can drop off. There are always exceptions, though. My "historians" group is exceptionally large, with 6 consistent members. What is most important is commitment. You must be committed to showing up, to sharing your work regularly, to giving a good reading of others' work, and to offering both support and accountability.

So, how do you start a group? Just ask around. Who in the department is at the same stage as you? Whose work, in or out of the department, do you find interesting? Maybe you have a friend in another department who has a suggestion. I think the Writing Center also has a general dissertation group, though I have no experience with it personally (do you?). I've had luck with simply asking friends or being asked. If any of you know of other avenues, though, please share! Also, check out Joan Bolker's advice.

As you get a group together, lay down some ground-rules. Decide how often will you meet––once a week, once a month? Will everyone share a small piece of writing at each meeting, or will one person sign up at a time? How will you balance being supportive with holding group members accountable for being productive? What you decide is less important than––once again––being seriously committed to the group.

What if you can't get a group started? When I've found myself without a group, I have still made sure to share my writing with various people on a one-on-one basis. (In fact, I still supplement my groups with on-on-one sharing.) As painful as it can be to share things that aren't "done" yet, talking to other people can help get you motivated, spark new ideas, and help remind you why you were excited about your project in the first place. And as much as you might feel reluctant to share, it's better (for your work and for your confidence) to share with a fellow grad student early on than to have your advisors' eyes be the first ones on it. Sharing is not just for when you have a complete first draft of a chapter and are starting to revise, it can also be for when you are stuck on a problem and need a new perspective. And you never know; sharing with one person may eventually lead to starting up a group.

Writing can be a lonely process. Particularly as a dissertator, it can be hard to know if you're on the right track. Holding yourself to a routine and personal deadlines is a constant struggle. With a good writing group, though, you don't have to do it all on your own.

Friday, January 13, 2012

Writing the dissertation from afar.

As someone who has done most of her post-prelims work away from Madison, I thought it might be good to say a few things about the rewards, challenges, and pitfalls of writing the dissertation from afar. I've done this for joyful reasons — falling in love, getting married, wanting to live in the same city, that kind of thing — but it's definitely an ongoing challenge, one I think about every day (while also missing Madison). The nice thing is that the self-directed nature of the dissertation makes these choices possible; the difficult thing is that it is really, really hard to keep on task when you are far away from your intellectual home. Fortunately, there are a lot of things that have made this a workable proposition for me.

The first is the amazing UW Libraries. They have an amazing program called Distance Services, which allows patrons who live outside of Dane County to request books online and receive the loans in the mail. They even include a prepaid return envelope, so when you're done, you simply slip the book back in and pop it in the mailbox. I've praised this service before on my own blog, but it is so fantastic that I can't say enough about it. Combined with electronic article delivery (another excellent UW Libraries service), Distance Services makes it possible for me to take advantage of the UW's world-class collections even though I don't live in Wisconsin. It has been both a lifeline and a life-saver for me as I have been writing.

The second reason I have been able to mostly stay on track with my work while being away from Madison is the support I have received from professors, committee members, and fellow students at the UW. Whether this has been regular telephone meetings to touch base, a Skype-based dissertator group to keep me writing my own stuff and reading others', or just a "hey there!" email that reminds me that I'm not alone — these contacts have kept my spirits up or restored them when I've been feeling discouraged. I feel so lucky to be surrounded (if not physically) by so many great and supportive friends, colleagues, and faculty.

Another group of people I have relied upon deserves special mention: the support staff who have kept me on track with all the administrative stuff that's so easy to forget when you're not on campus — things like registering for HistSci 990 (the "I'm writing my dissertation now" class) and making sure I have all my information up-to-date. These folks — including our own Department Administrator, Eileen Ward, and the Fellowship Coordinators like Mary Butler Ravneburg at Bascom Hall — have been super accessible by phone and email, have been willing to make phone calls on my behalf and do legwork for me when something has gone awry or when I have had questions, and have even telephoned me when I'm about to miss a deadline. Their work is so often invisible and unsung, but it's what keeps this place running, and they have my gratitude.

Now the hard parts. Being away from one's intellectual home while one is engaged in the most challenging part of the phone Ph.D. process — actually writing that gosh-darned dissertation — is really, really, really difficult. Way harder than you think it will be. It's lonely (even lonelier than it usually is), and the matter of remaining motivated, on-task, and upbeat when no one is there keeping an eye on you, and when you don't really have a firm schedule, and when you don't have talks to go to or meetings to attend or the general campus stuff to structure your days, can be very tough indeed. (Basically, it has all the problems of writing the dissertation without being away — the problems are just compounded and intensified.)

Having been away from the UW on and off for a few years now, depending on my funding, I have come up with some strategies for writing your dissertation from afar. I'm hoping this will open up a wider forum for these issues, as I know I'm not the only person to have done this, and I'm sure there are many of us out here who would like to be able to swap stories and share ideas for how to keep on task.

- Write every day. This is the cardinal rule for the dissertation, whether you're away from your home institution or not, and it's in some ways the hardest one to follow. I know I've had a terrible time getting into a really solid writing routine, though part of that has had to do with my constant moving over the past year, which makes the writing really hard (see below). But writing every day, during the time when your brain is most active and alert, even if you only have one idea or write only one paragraph, is really the key to keeping the momentum going, the gears turning, and the pages coming.

- Develop a routine. This is one thing that's been difficult for me, as I've been moving around a lot this year, and moving takes a lot of time and energy. Every time I get into the swing of a routine, it has suddenly been time to change my location, forcing me to carve out a new groove for myself. Having five months in the same place, as I do right now, feels like a luxury, and I am ready to take advantage of it.

- Find a place to write. Again, this has been a challenge for me, as I do not work well at home (too many distractions), but I have been fortunate in securing an office during my brief stint at Cornell this summer, and this spring at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Even if your place is just the coffeeshop around the corner, the library, or even a set-aside corner of your apartment that you don't use for other activities, having a spot that is dedicated to writing really helps.

- Take breaks. While it's important to keep your focus on your output, "writing" is actually a whole cluster of activities — including thinking, sleeping, notetaking, daydreaming, talking, story-crafting, and reading — that ultimately result in coherent words on the page. I've found that going for walks is really helpful to my thinking. Sometimes it's best for me to go on them alone, other times I like to have a walking-and-talking companion, but I almost always return from any kind of walk feeling very glad that I took it.

- Nurture your support system. Having people to discuss writing and ideas with (not to mention to kvetch, complain, and commiserate with) is really, really important. Assembling a writing group that meets regularly is also a great way to impose deadlines on yourself and on one another in ways that no one else will do for you when you're at this stage. With VoIP and videoconferencing technology like Skype and Google Voice, you can even carry on a dissertator group with members all over the world, as long as you have a decent internet connection. This also helps you not become a huge annoyance to anyone you happen to be living with, or who is otherwise forced to come into contact with you regularly while you are going through the throes of writing. These people are just as important as your intellectual cohort, and you should be nice to them, for they will sometimes make you dinner or bring you a cup of tea or offer a welcome break from writing when you really need it.

- Focus on the dissertation, not what comes after. If you're on the job market, like me, applications and cover letters and research statements and all that can be a huge drain on time that really could be spent writing. I have tried to streamline this process by getting a good set of documents together for different purposes and different kinds of jobs (using a dossier service like Interfolio has been a big help) so that when a deadline approaches, I don't have to do too much scurrying around to get all my materials together and sent. What I keep reminding myself: no one will hire you if the dissertation isn't done, so writing is more important than applying.